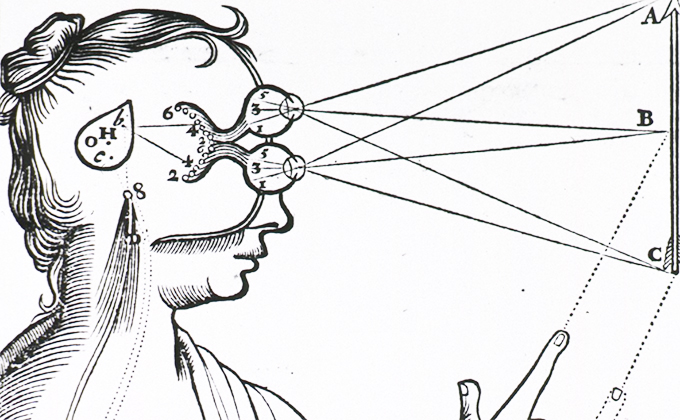

One of the deepest and most lasting legacies of Descartes’ philosophy is his thesis that mind and body are really distinct—a thesis now called “mind-body dualism.” He reaches this conclusion by arguing that the nature of the mind (that is, a thinking, non-extended thing) is completely different from that of the body (that is, an extended, non-thinking thing), and therefore it is possible for one to exist without the other. This argument gives rise to the famous problem of mind-body causal interaction still debated today: how can the mind cause some of our bodily limbs to move (for example, raising one’s hand to ask a question), and how can the body’s sense organs cause sensations in the mind when their natures are completely different?

The mind–body problem

The mind–body problem is the problem of explaining how mental states, events and processes—like beliefs, actions and thinking—are related to the physical states, events and processes, given that the human body is a physical entity and the mind is non-physical.

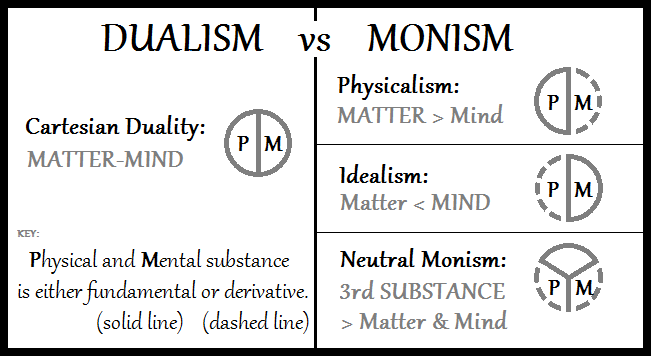

The problem was addressed by René Descartes in the 17th century, resulting in Cartesian Dualism, and by pre-Aristotelian philosophers, in Avicennian philosophy, and in earlier Asian traditions. A variety of approaches have been proposed. Most are either dualist or monist. Dualism maintains a rigid distinction between the realms of mind and matter. Monism maintains that there is only one unifying reality, substance or essence in terms of which everything can be explained.

Each of these categories contains numerous variants. The two main forms of dualism are substance dualism, which holds that the mind is formed of a distinct type of substance not governed by the laws of physics, and property dualism, which holds that mental properties involving conscious experience are fundamental properties, alongside the fundamental properties identified by a completed physics. The three main forms of monism are physicalism, which holds that the mind consists of matter organized in a particular way; idealism, which holds that only thought truly exists and matter is merely an illusion; and neutral monism, which holds that both mind and matter are aspects of a distinct essence that is itself identical to neither of them.

Several philosophical perspectives have been developed which reject the mind–body dichotomy. The historical materialism of Karl Marx and subsequent writers, itself a form of physicalism, held that consciousness was engendered by the material contingencies of one’s environment. An explicit rejection of the dichotomy is found in French struturalism, and is a position that generally characterized post-war French philosophy.

René Descartes’ idea and critics

René Descartes usually called the “father of modern philosophy”. He broke with the past and gave philosophy a fresh start. Descartes talks of demolishing everything completely and starting again right from the fundations’, and for this purpose he famously uses doubt, stretched to its limits, as an instrument which self destructs, impelling him forward to the journey towards certainty and truth. He set the agenda for subsequent discussions of the mind–body relation. According to Descartes, minds and bodies are distinct kinds of substance. Bodies, he held, are spatially extended substances, incapable of feeling or thought; minds, in contrast, are unextended, thinking, feeling substances.

In the Discourse, Descartes presented the following argument to establish that mind and body are distinct substances:

Next I examined attentively what I was. I saw that while I could pretend that I had no body and that there was no world and no place for me to be in, I could not for all that pretend that I did not exist. I saw on the contrary that from the mere fact that I thought of doubting the truth of other things, it followed quite evidently and certainly that I existed; whereas if I had merely ceased thinking, even if everything else I had ever imagined had been true, I should have had no reason to believe that I existed. From this I knew I was a substance whose whole essence or nature is simply to think, and which does not require any place, or depend on any material thing, in order to exist.

This argument moves from the fact that he can doubt the existence of the material world, but cannot doubt the existence of himself as a thinking thing, to the conclusion that his thoughts belong to a non-spatial substance that is distinct from matter.

In the Meditations, Descartes changed the structure of the argument. In the Second Meditation, he established that he could not doubt the existence of himself as a thinking thing, but that he could doubt the existence of matter. However, he explicitly refused to use this situation to conclude that his mind was distinct from body, on the grounds that he was still ignorant of his nature. Then, in the Sixth Meditation, having established, to his satisfaction, the mark of truth, he used that mark to frame a positive argument to the effect that the essence of mind is thought and that a thinking thing is unextended; and that the essence of matter is extension and that extended things cannot think. He based this argument on clear and distinct intellectual perceptions of the essences of mind and matter, not on the fact that he could doubt the existence of one or the other.

This conclusion in the Sixth Meditation asserts the well-known substance dualism of Descartes. That dualism leads to problems. If minds and bodies are radically different kinds of substance, however, it is not easy to see how they could causally interact Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia puts it forcefully to him in a 1643 letter

…how the human soul can determine the movement of the animal spirits in the body so as to perform voluntary acts—being as it is merely a conscious substance. For the determination of movement seems always to come about from the moving body’s being propelled—to depend on the kind of impulse it gets from what sets it in motion, or again, on the nature and shape of this latter thing’s surface. Now the first two conditions involve contact, and the third involves that the impelling thing has extension; but you utterly exclude extension from your notion of soul, and contact seems to me incompatible with a thing’s being immaterial…

Elizabeth is expressing the prevailing mechanistic view as to how causation of bodies works… Causal relations countenanced by contemporary physics can take several forms, not all of which are of the push–pull variety.

This problem vexed not only Descartes, who admitted to Elisabeth that he didn’t have a good answer, but it also vexed Descartes’ followers and other metaphysicians. It seems that, somehow, states of the mind and the body must be brought into relation, because when we decide to pick up a pencil our arm actually moves, and when light hits our eyes we experience the visible world. But how do mind and body interact? Some of Descartes’ followers adopted an occasionalist position, according to which God mediates the causal relations between mind and body; mind does not affect body, and body does not affect mind, but God gives the mind appropriate sensations at the right moment, and he makes the body move by putting it into the correct brain states at a moment that corresponds to the volition to pick up the pencil. Other philosophers adopted yet other solutions, including the monism of Spinoza and the pre-established harmony of Leibniz.

In the Meditations and Principles, Descartes did not focus on the metaphysical question of how mind and body interact. Rather, he discussed the functional role of mind–body union in the economy of life. As it happens, our sensations serve us well in avoiding harms and pursuing benefits. Pain-sensations warn us of bodily damage. Pleasure leads us to approach things that (usually) are good for us. Our sense perceptions are reliable enough that we can distinguish objects that need distinguishing, and we can navigate as we move about. As Descartes saw it, “God or nature” set up these relations for our benefit. They are not perfect. Sometimes our senses present things differently than they are, and sometimes we make judgements about sensory things that extend beyond the appropriate use of the senses.