GOETHE, JOHANN WOLFGANG von (1749-1832), the most renowned poet of German literature, was already from his youth deeply interested in the East and in Islam. He planned to write a drama about Moḥammad, as witnessed by the poem Mahomets-Gesang. But it was not until later, during his period of romanticism, that the poet devoted his attention to the literature and history of Persia. Goethe considered literature (language) and religion as the best aids to discovering other cultures. In addition to Persian literature, he also learned the Arabic language and script and studied the teachings of Zoroaster as well as those of Islam. Goethe’s productive preoccupation with Persia goes back to the years 1814 to 1827; and it was, above all, his acquaintance with Ḥāfeẓ which increasingly awakened his interest in Persian literature.

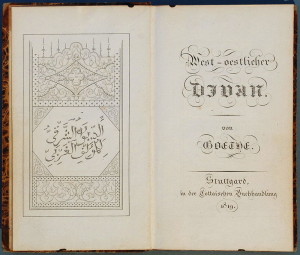

Goethe’s West-östlicher Divan (West-Eastern Divan) marks a literary encounter between German and Persian literature which began in 1814. In the spring of that year, Goethe received a German translation of Ḥāfeẓ’s divān in two volumes from the publisher Cotta of Stuttgart. The translator was the Austrian Orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774-1856), whose translations and commentaries played a major role in acquainting Germans with the East. Hammer’s translation of the divān broadened and expanded the knowledge of the Orient which Goethe had acquired in his youth, so that he could now, at the age of 65, devote himself more intensively to the East, and predominantly to Persia.

Goethe’s approach to Ḥāfeẓ began with enthusiasm, which, in its turn, led to interchange and dialogue, and, in the Divan, assumed a lyric-prosaic form. The need for communication, for narrative and for finding one’s way into a different society is characteristic of the essence of the Divan. The dialogue with Ḥāfeẓ, however, demanded a knowledgeable analysis of the Oriental world. For this there was no lack of material; for, apart from the works of such travelers to the Orient as Marco Polo, Pietro della Valle, and Adam Olearius, and, above all, the translations of Saʿdi’s Golestān and Bustān, Goethe also read works by Orientalists, such as the Denkwürdigkeiten aus Asien (1813-15) by Heinrich Friedrich von Diez, the journal Fundgruben des Orients (1809-14), and Hammer’s Geschichte der Schönen Redekünste Persiens (1818).

In the prose section Goethe refers to imperfections in his work and to a plan for a Künftiger Divan; he also explains how he went about his Oriental studies. His arguments about Eastern poetry, as well as about the Christian Orient (Israel in der Wüste), are fully represented (Lentz, 1957, pp. 180 ff.). Goethe’s preoccupations with travel descriptions by visitors to the East, as well as German translations of Oriental works, which formed the source of his own knowledge about the East, are also discussed in this part. A characteristic mark of this less lyrical and more prosaic part of the Divan is Goethe’s passage from travelers to the Orient to Orientalists (Goethe, 1998a, pp. 245-58), which simultaneously marks an evolution from descriptions based on personal experience to scholarly accounts of the East. Among the main activities of Orientalists was translating from Oriental languages; Goethe ends his Divan with a chapter reflecting on the problems of translation.

The title West-östlicher Divan (West-Eastern Divan) is ambivalent, and shows that the work is not to be understood unidimensionally, but as a dialogue. A discussion takes place which begins as a lyrical dialogue between Goethe and Ḥāfeẓ, but later expands to encompass East and West. When considering not only the work’s title, but its content as well, the ambiguity becomes even more obvious. The incentive provided by Ḥāfeẓ prompts the German poet to make a fictitious journey to the East, where the competition between poetry and religion, a favorite theme of both poets, leads to instructive discussions. The eastward journey—which, with its initial poem, “Hegire,” in the Buch des Sängers, marks the beginning of a new phase in life—and the sojourn in the east also characterize this lyrical work as poetry based on personal experience. This poetry shows Goethe’s wealth of imagination—an imagination steadily nourished by Ḥāfeẓ—through masquerades and role-playing, irony, jest and (West-Eastern Divan).

The title West-östlicher Divan (West-Eastern Divan) is ambivalent, and shows that the work is not to be understood unidimensionally, but as a dialogue. A discussion takes place which begins as a lyrical dialogue between Goethe and Ḥāfeẓ, but later expands to encompass East and West. When considering not only the work’s title, but its content as well, the ambiguity becomes even more obvious. The incentive provided by Ḥāfeẓ prompts the German poet to make a fictitious journey to the East, where the competition between poetry and religion, a favorite theme of both poets, leads to instructive discussions. The eastward journey—which, with its initial poem, “Hegire,” in the Buch des Sängers, marks the beginning of a new phase in life—and the sojourn in the east also characterize this lyrical work as poetry based on personal experience. This poetry shows Goethe’s wealth of imagination—an imagination steadily nourished by Ḥāfeẓ—through masquerades and role-playing, irony, jest and (West-Eastern Divan).

The twelve books of the Divan can be interpreted as a reflection of Goethe’s Oriental studies. To begin with, the reader’s attention is drawn to its structure, for this is the first time that Goethe divides a work into “books.” Each book bears a double title: a Persian title, followed by a German one, with the word nameh (Pers. nāma)/Buch as the first component. (This is similar to Saʿdi’s method in the Golestān) The Divan opens with the Moghani Nameh/Buch des Dichters (later Buch des Sängers),which has as its main theme the poet’s “Hegira” to the East and his acquaintance with Oriental culture. This is followed by Hafis Nameh/Das Buch Hafis, which is devoted to characterization and admiration of the Persian poet, and in which Ḥāfeẓ assumes the central role of interlocutor. The third book, Uschk Nameh/Buch der Liebe, discusses love and passion; there is a thematic relationship between this book and the Buch Suleika, although the name Suleika is not mentioned in the Book of Love. The Tefkir Nameh/Buch der Betrachtungen has a didactic and moral character. Rendsch Nameh /Buch des Unmuts contains political and social criticism. Hikmat Nameh/Buch der Sprüche closely resembles the Buch der Betrachtungen and Buch des Unmuts, centering on Oriental adages and the art of poetry. Timur Nameh/Buch des Timur is devoted to the conqueror Timur, Ḥāfeẓ’s contemporary, whom Goethe considered as resembling his own contemporary Napoleon; it is linked with the ensuing Suleika Nameh/Buch Suleika by the poem “An Suleika”. The Buch Suleika takes the form of a dialogue between the Arab Hatemand the Persian Suleika, who figures the poet and his beloved Marianne; a number of Marianne’s own poems are included. Monologues and dialogues of a totally different kind are found in the Saki Nameh/Das Schenkenbuch, with its Anacreontic tone, which Goethe had already used in his younger days and which he now imitates in the style of Ḥāfeẓ. Mathal Nameh/Buch die Parabeln contains fables and parables; Parsi Nameh/Buch des Parsen deals with the Old Persian adoration of fire and the sun. The final book, Chuld Nameh/Buch des Paradieses, blends Islamic conceptions of paradise with those of the poet himself.

In his Noten und Abhandlungen Goethe paid tribute to several other Persian poets: Ferdowsi, Anwari, Neẓāmi, Rumi, Saʿdi, and Jāmi. But Ḥāfeẓ was the only one to whom he devoted an entire book. In his Zwillingsbruder he had discovered a poet whose inspiration awakened in him a feeling of rejuvenation. And although in some cases a critical distance can be felt in Goethe’s approach to the form of Ḥāfeẓ’s poetry, he nevertheless felt inspired to write ḡazals; an example is the last poem of the Buch Suleika. In many poems he employs a “signature verse” (taḵallosá) typical of the ḡazal, in which he addresses, refers to, or identifies with the Persian poet. But Goethe’s attempts at writing ḡazals came up against his own criticism, which he expressed in the poem Nachbildung by criticizing the formal constraint of using monorhyme. But while Goethe preferred a unified and logical whole—and here he remains Western—he followed closely the thematics and imagery of Ḥāfeẓ’s poetry. In the Buch des Sängers and the Buch Hafis, where Ḥāfeẓ’s name is most often mentioned, motifs and characters from the latter’s poetry form the Persian mask of the Divan.

Ḥāfeẓ’s inspiration was so strong that in some of his poems Goethe called him heiligen Hafis or Meister. In other books, although Ḥāfeẓ’s name is not mentioned, his proximity can be felt through allusions and hints. A theme shared by both poets was that of poetic madness, already well-known in European literature. As in Ḥāfeẓ’s work, panegyrics, Anacreontics, mysticism, and eroticism formed the motifs of Goethe’s Divan, in which passion and intellect, mysticism and irony, love and common sense were equally present. Through Ḥāfeẓ, Goethe was able to express his own moral and political criticism of his time. A significant aspect of Ḥāfeẓ’s work appears in Goethe merely by implication: Ḥāfeẓ’s rendi (libertinism) is recognized but never appears as such, although Goethe did use Persian words. Allusions to rendi can be found both in the Buch Hafis and the Schenkenbuch.

Goethe’s encounter with Ḥāfeẓ was highly significant for the history of German poetry. His Divan is generally considered as an east-western work containing both foreign and native elements. Goethe’s poetic art consists of mixing foreign and indigenous elements by creating a dialogue between two poets: the German poet of Weimar and the Persian poet of Shiraz. The last great collection of poems by the classicist Goethe thus marks a major stage in the development of lyric poetry in general.

According to Hamid Tafazoli, the great German poet became aware of and was influenced by the ideas of Hafiz, who had preceded him nearly by four centuries. Despite the time lapse, both had quite similar philosophies of life and viewed their contemporary social and political conditions with comparable outlooks. So deep were the similarity of values and attitudes that Goethe proceeded to embark on an imaginary trip to the land of Hafiz, which produced one of the German poet’s major works entitled West-oestlicher Divan (West–Eastern Diwan).

Despite the complexity of its ideas and expressions, this masterpiece opened a new vista in the German classical and romantic period which in turn introduced the rest of Europe to Iranian culture and its literary and poetic achievements. Since 1814, Goethe diverted his full attention to the study of Oriental and Eastern culture and literature. The publication of a German translation of Divan of Hafiz in the same year had introduced him to the Persian poet. In his imaginary trip, Goethe proceeded from China to India and Arabia and finally settled in Iran, the land of Hafiz whom he called his twin brother.

Goethe, in the writing of West-oestlicher Divan, was influenced by three main characteristics evident in both Hafiz’ poetry and Eastern culture. The first was Hafiz’ masterful juxtaposition of worldly feelings and metaphysical/mystic sensations. The second was the Persian poet’s style that liberated Goethe from the confines of traditional European poetic forms. The third was the pervasive values in Iranian culture that in Goethe’s view had traversed geographic boundaries and engulfed all Eastern World.

West-östlicher Diwan (West–Eastern Diwan, original title: West-östlicher Divan) is a diwan, or collection of lyrical poems, by the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. It was inspired by the Persian poet Hafez. West–Eastern Divan was written between 1814 and 1819, the year when it was first published. It was inspired by Goethe’s correspondence with Marianne von Willemer and the translation of Hafez’ poems by the orientalist Joseph von Hammer. An expanded version was printed in 1827. It is part of Goethe’s late work and the last great cycle of poetry he worked on. The initial issue consisted of twelve books:

- Book of the Singer (Moganni Nameh)

- Book of Hafiz (Hafis Nameh)

- Book of Love (Uschk Nameh)

- Book of Reflection (Tefkir Nameh)

- Book of Ill Humour (Rendsch Nameh)

- Book of Maxims (Hikmet Nameh)

- Book of Timur (Timur Nameh)

- Book of Zuleika (Suleika Nameh)

- Book of the Cupbearer (Saki Nameh)

- Book of Parables (Mathal Nameh)

- Book of the Parsees (Parsi Nameh)

- Book of Paradise (Chuld Nameh)

The work can be seen as a symbol for a stimulating exchange and mixture between Orient and Occident. The phrase “west–eastern” refers not only to an exchange between Germany and the Middle East, but also between Latin and Persian culture, as well as the Christian and Muslim cultures. The twelve books consist of poetry of all different kinds: parables, historical allusions, pieces of invective, politically or religiously inclined poetry mirroring the attempt to bring together Orient and Occident. For a better understanding, Goethe added “Notes and Queries”, in which he comments on historical figures, events, terms and places.

sources: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/goethe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wesstlicher_Divan