Epicureans thought human existence was just a random groupings of atoms that fell apart after death. Their motto was “don’t worry, be happy”. Epicurus tries to construct a system of simple, coherence, and plausible principles. he is a hedonist who regards the fear of death as the most dangerous source of fear, insecurity, and unhappiness.

Epicurean’s Ethics:

Epicurus’ ethical theory rests on his hedonism – his belief that pleasure is the ultimate good, and other things are good only to the extent that they are means to pleasure. He believed that all animals immediately recognize that pleasure is good, and pursue it as their end; children pursue it spontaneously before they have acquired any other beliefs about what is good.

For Epicureans morality may be a necessary condition of attaining maximum pleasure, but morality would be nothing if it did not produce pleasure. Above the entrance of their school were the words: Pleasure is the highest good”.

For Epicureans morality may be a necessary condition of attaining maximum pleasure, but morality would be nothing if it did not produce pleasure. Above the entrance of their school were the words: Pleasure is the highest good”.

The Epicurean wants to regulate his desires so that they do not make him dependent on external fortune; he therefore values the results of temperance. He does not fear the loss of worldly goods, since he does not need many; he is therefore not tempted to act like a coward. He finds mutual aid in the society and friends, and so he cultivates friendship.

The epicurean is not greedy for power or dominion over others. He finds it a source of anxiety and insecurity. Since he values freedom from anxiety, he will want to avoid the risk of detention and punishment.

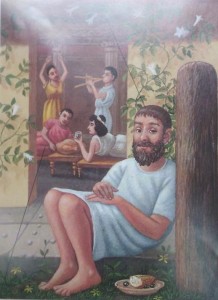

Epicurus’ idea of pleasure was to enjoy the simple things in life. Plenty of time to relax was top of the list. He much preferred a simple meal eaten with friends than risk a tummy upset on a lavish banquet. In fact he urged followers to think twice before pursuing any pleasure than might cause pain. Even falling in love can end in a broken heart. Epicurus’ followers were called “garden philosophers” because he founded his school in a garden near Athens.

Fear death and fear punishment after death:

We conduct our lives badly because we fear death; and we fear death because we fear punishment after death. Epicurus thinks that fear of death underlies all the acquisitive and competitive aspects of our lives; indeed, he thinks it explains our tendency to accept a Harmonic outlook. Fearing death, we try to assure ourselves of security and protection against other people. The search for security leads us to pursue power, wealth, and honour, and makes us constantly afraid of losing them. We seek posthumous fame and honour, as Achilles did, because we refuse to admit to ourselves that we will not be present to enjoy it; and our fear of death explains why we refuse to admit that we will not be present.

We conduct our lives badly because we fear death; and we fear death because we fear punishment after death. Epicurus thinks that fear of death underlies all the acquisitive and competitive aspects of our lives; indeed, he thinks it explains our tendency to accept a Harmonic outlook. Fearing death, we try to assure ourselves of security and protection against other people. The search for security leads us to pursue power, wealth, and honour, and makes us constantly afraid of losing them. We seek posthumous fame and honour, as Achilles did, because we refuse to admit to ourselves that we will not be present to enjoy it; and our fear of death explains why we refuse to admit that we will not be present.We occupy ourselves in constant activity and competition, to conceal our fear of death from ourselves. we do not realize that fear of death is our basic motive; each of us “flees from himself”; we need occupations to divert us from the oppressive awareness of ourselves and our fears, but we do not know why we find the awareness of ourselves so oppressive. To remove our fears, both the known and the acknowledged, we need an account of the universe that gives us no reason to fear death. We fear ourselves from fear once we believe that the universe in not controlled by gods who determine or modify natural processes for their own purposes, and that we do not survive death. If we have reason to believe this, then (in Epicurus’s view) we have no reason to think death does any harm to us; hence we have no reason to fear death; hence we no longer fear death.

Epicurus wants to show that the soul is a collection of atoms, just as trees and chairs are, and therefore is just as certain to decay and dissolve into constituents. If Epicurus is right about this, then Plato cannot be right to believe in an immaterial and immortal soul. If we do not believe in immortality, we will not believe that we can suffer harm after death, and therefore, Epicurus thinks, we have no reason to fear death and will not fear death.

The existence of any designing gods:

To show that the gods are no concerned with the world, Epicurus attacks a particular teleological doctrine. Plato and Stoics argue that the order in individual organisms depends on the larger order that maintains them, and this order is plausibly explained as the product of intelligent design. The order in the world supplies an argument for the existence of a designing god.

In reply Epicurus holds that the disorder in the world tells against the existence of any designing gods. Natural disasters and other apparent imperfections suggest that only non-purposive forces could control the processes in the world – unless the gods are remarkably stupid, malicious, or incompetent. The flaws in the observed character of the world confirm the atomic theory, and undermine belief in gods who care about the world.

In reply Epicurus holds that the disorder in the world tells against the existence of any designing gods. Natural disasters and other apparent imperfections suggest that only non-purposive forces could control the processes in the world – unless the gods are remarkably stupid, malicious, or incompetent. The flaws in the observed character of the world confirm the atomic theory, and undermine belief in gods who care about the world.Though Epicurus denies that the gods design or control the world order, he believed that empiricism requires him to accept gods. For in dreams and visions people claim to be aware of gods; and something external must correspond to their perceptions, since all perceptions are true, but the only external things that could correspond to their perceptions are immortal, intelligent, and blessedly happy beings looking like human beings with human bodies. The gods, like everything else with human or animal bodies, must be composed of atoms; but they are not destroyed in the way other collections of atoms are destroyed, since they live between the worlds that are subject to destruction, and so avoid the atomic forces that destroyed other collections of atoms.

But Epicurus raises a serious questions: Why should an invulnerable and blessed being interest himself in the world or in us? Why should they want to create a world, if they are already completely happy and need nothing more? However, in antiquity Epicureanism was often brusquely dismissed. Its anti-religious tendencies (real or supposed) aroused suspicion; and its hedonism was sometimes misinterpreted as advocacy of immoral self-indulgence.