In the early twentieth century the French sociologist Robert Hertz published an influential essay under the title of “A Contribution to the Study of the Collective Representation of Death.” Hertz’s primary interest was in the quite widespread Malayo-Polynesian practice of double burial, whereby corpses were not immediately taken to a final resting place but instead placed in a temporary location such as the family house for a period of time. It was said that the corpse should not be permanently buried until it had thoroughly decomposed so that only the bones remained. Bodies allowed to rot in this way were sometimes sealed in coffins and the putrefying liquids drained from time to time. In certain parts of Borneo relatives of the deceased mixed this decomposing material with rice, eaten during the period of mourning. Hertz observed that the condition of the corpse corresponded to the imagined condition of the dead person’s soul. While the corpse was rotting, the soul was considered to remain in a kind of limbo and could not find rest until the decomposing material had drained away, leaving only the dried skeletal remains. By eating the fleshy part of the corpse, mourners hoped to expedite the process of drying out considered necessary for the release of the soul, but these act of endo-cannibalism also provided a means of consuming the vitality of the corpse, the flesh that made the person strong and active during life but which must now be left behind. This vitality is of value to the living inasmuch as society requires strong and healthy members.

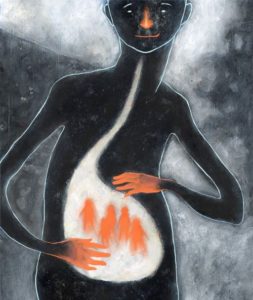

In the early twentieth century the French sociologist Robert Hertz published an influential essay under the title of “A Contribution to the Study of the Collective Representation of Death.” Hertz’s primary interest was in the quite widespread Malayo-Polynesian practice of double burial, whereby corpses were not immediately taken to a final resting place but instead placed in a temporary location such as the family house for a period of time. It was said that the corpse should not be permanently buried until it had thoroughly decomposed so that only the bones remained. Bodies allowed to rot in this way were sometimes sealed in coffins and the putrefying liquids drained from time to time. In certain parts of Borneo relatives of the deceased mixed this decomposing material with rice, eaten during the period of mourning. Hertz observed that the condition of the corpse corresponded to the imagined condition of the dead person’s soul. While the corpse was rotting, the soul was considered to remain in a kind of limbo and could not find rest until the decomposing material had drained away, leaving only the dried skeletal remains. By eating the fleshy part of the corpse, mourners hoped to expedite the process of drying out considered necessary for the release of the soul, but these act of endo-cannibalism also provided a means of consuming the vitality of the corpse, the flesh that made the person strong and active during life but which must now be left behind. This vitality is of value to the living inasmuch as society requires strong and healthy members.Endocannibalism is a practice of eating the flesh of a human being from the same community (tribe, social group of society), usuallt after they have died.

When a person dies, his or her body is destroyed and along with it the particular hopes, fears, loves and hates of the individual. But what of the social roles and obligations that person had acquired over the course of a lifetime? These must somehow be redistributed and preserved. The transition may be awkward, however. If the deceased was a pillar of community, upon whom many depended, death would be a source of major social disruption. Hertz believed that in the small-scale society of Borneo, where social cohesion was strong, the disruption caused by death was experienced as kind of outrage against the group itself. Death destroyed not only the profane, biological part of the person but also the social or sacred aspect, and the purpose of the double funeral was to correct this outrage, to respond to the sacrilege of death.

Source: Harvey Whitehouse, Immortality, creation, and regulation, Ubdating Durkheim’s theory of the sacred, in Mental Culture, edited by: Dimitris Xygalatas and William W. Mc Corkle Jr.