Of all Buddhist doctrines, possibly the most difficult — and misunderstood — is shunyata. Often translated as “emptiness,” shunyata is at the heart of all Mahayana Buddhist teaching. It is often misunderstood to mean that nothing exists. This is not so. Instead, it tells us that there is existence, but that phenomena are empty of svabhava, a Sanskrit word that means self-nature, intrinsic nature, essence, or “own being.”

Of all Buddhist doctrines, possibly the most difficult — and misunderstood — is shunyata. Often translated as “emptiness,” shunyata is at the heart of all Mahayana Buddhist teaching. It is often misunderstood to mean that nothing exists. This is not so. Instead, it tells us that there is existence, but that phenomena are empty of svabhava, a Sanskrit word that means self-nature, intrinsic nature, essence, or “own being.”

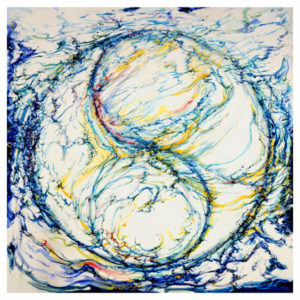

Shunyata, in Buddhist philosophy, the voidness that constitutes ultimate reality; shunyata is seen not as a negation of existence but rather as the undifferentiation out of which all apparent entities, distinctions, and dualities arise. Although the concept is encountered occasionally in early Pāli texts, its full implications were developed by the 2nd-century Indian philosopher Nāgārjuna. The school of philosophy founded by him, the Mādhyamika (Middle Way), is sometimes called the Śūnyavāda, or Doctrine That All Is Void.

Because the Madhyamika recognised nothing in the conceptual realm as ultimately or absolutely real, it came to be known as the philosophy of shunyata, or relativism. Shunyavadins call themselves Madhyamika or the followers of the Middle path realized by Buddha during his enlightenment, which path, avoiding the errors of existence and non-existence, affirmation and negation, eternalism and nihilism, also at once transcends both the extremes.

Because the Madhyamika recognised nothing in the conceptual realm as ultimately or absolutely real, it came to be known as the philosophy of shunyata, or relativism. Shunyavadins call themselves Madhyamika or the followers of the Middle path realized by Buddha during his enlightenment, which path, avoiding the errors of existence and non-existence, affirmation and negation, eternalism and nihilism, also at once transcends both the extremes.

Nagarjuna felt that the Thervada philosophers were getting carried away with their categories of dharmas used to explain reality. He advocated a turn to the position of silence adopted by the Buddha when he refused to answer metaphysical questions, In place of the dharmas suggested by Thervadins, Madhyamika philosophy asserts that nothing is real; all is void, or shunyata. Shunyata is the emptiness behind all appearances. It is the nothing that serves as the foundation for human experiences.

Nagarjuna argued that there is nothing that can be said about existence. Words are not reliable and cannot be trusted to tell us the truth. Even the distinction between existence and non-existence is invalid. This means philosophical speculation fails to supply adequate answers about the nature of reality. Recognizing the uselessness of philosophical speculation is a step forward in becoming liberated from worldly things. Nagarjuna said that it is incorrect to say that things exist, but it is also incorrect to say that they don’t exist. Because all phenomena exist interdependently, and are void of self-essence, all distinctions we make between this and that phenomena are arbitrary and relative. So, things and beings “exist” only in a relative way.

Nagarjuna argued that there is nothing that can be said about existence. Words are not reliable and cannot be trusted to tell us the truth. Even the distinction between existence and non-existence is invalid. This means philosophical speculation fails to supply adequate answers about the nature of reality. Recognizing the uselessness of philosophical speculation is a step forward in becoming liberated from worldly things. Nagarjuna said that it is incorrect to say that things exist, but it is also incorrect to say that they don’t exist. Because all phenomena exist interdependently, and are void of self-essence, all distinctions we make between this and that phenomena are arbitrary and relative. So, things and beings “exist” only in a relative way.

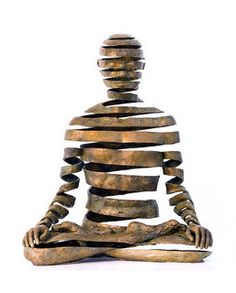

Using the concept of shunyata, Madhyamika aims at going further than other Buddhists in dissolving the self. Not only the self and one’s ideas are illusory, but the world itself is no more than an appearance. What’s more, this appearance does not disguise emptiness, but is emptiness. When properly understood, reality is empty. The point is to reject the impulse to try to make something (or nothing!) out of anything. All attempts to conceptualize actuality bind us to delusion. To fully understand this is to attain enlightenment.

Nagarjuna’s critics objected that if we accept the idea of emptiness, the basic teachings of Buddhism, including the Four Noble truths and the Eightfold Path, have to go out the window, too. After all, these are conceptualizations; therefore, they must be invalid like all the others. Nagarjuna responded by saying that the truth of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path are conventional and relative truths. They are helpful in pointing the direction on the ultimate truth of shunyata, and therefore are valuable. But these teachings should not be mistaken for exact descriptions of the nature of reality – for tathata, or suchness. This is indescribable and beyond conceptualization.

Nagarjuna’s critics objected that if we accept the idea of emptiness, the basic teachings of Buddhism, including the Four Noble truths and the Eightfold Path, have to go out the window, too. After all, these are conceptualizations; therefore, they must be invalid like all the others. Nagarjuna responded by saying that the truth of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path are conventional and relative truths. They are helpful in pointing the direction on the ultimate truth of shunyata, and therefore are valuable. But these teachings should not be mistaken for exact descriptions of the nature of reality – for tathata, or suchness. This is indescribable and beyond conceptualization.

The concept of shunyata – the void – could be used to deny the distinction between all concepts. In fact, Nagarjuna himself used it to challenge the distinction between nirvana and samsara. He suggested that attempts to free the self of desires could be understood as actually motivated by desire. On the other hand, the serene acceptance of desired things can indicate that desire has been transcended. As long as we are conceptualizing anyway, it’s all relative.

The concept of emptiness, the void, vacuity, has been employed in the Madhyamika teaching as a convenient and effective pedagogical instrument to bring the mind beyond that sense of duality which infects all systems in which the absolute and the world of relativity are described in contrasting, or antagonistic terms. But the circumstance to be borne in mind that this Buddhist philosophy is not primarily an instrument of reason but an instrument to convert into realization; one step beyond the term is the understanding of what is really means. And as a device to effect such a transformation of knowledge – first standing between all the contraries of “the world” and “release from the world”, then standing between the moment of preliminary comprehension and that of realized illumination – it would be difficult indeed to find a more apt and efficient term. This is why the doctrine is called Madhyamika, the “Middle Way”. And actually, it brings, as far as possible, into systematic philosophical statement the whole implication of the “Middle Doctrine” of the Buddha himself that the extremes have been avoided by the Tathagata, and therefore it is a middle doctrine that he teaches. The Buddha continually diverted the mind from its natural tendency to posit an abiding essence beyond, or underlying, the endless and meaningless dynamism of the concatenation of causes. And this is the effect also of Nagarjuna’s doctrine of the void.