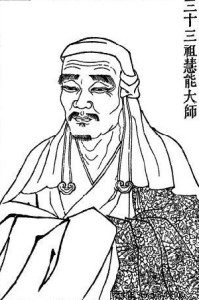

Let’s start with the story of Hui-neng, the Sixth patriarch of Zen Buddhism.

The Fifth Patriarch of Zen Buddhism – and here we begin to enter a more reliable chapter of history – was Hung-jen (601-675). Who was apparently the first of the patriarchs to have any large following, however, much overshadowed by his immediate successor Hui-neng (637-713), the sixth Patriarch, whose life and teaching mark the definitive beginning of truly Chinese Zen – of Zen as it flourished during what was later called “the epoch of Zen activity,” the latter two hundred years of the T’ang dynasty, from about 700 to 906. Hui-neng’s original satori (the Zen experienced awakening) occurred spontaneously, without the benefit of a master and that his biography represents him as an illiterate peasant. Apparently Hung-jen immediately recognized the depth of his insight, but fearing that his humble origins might make him unacceptable in a community of scholarly monks, the Patriarch put him to work in the kitchen compound.

The Fifth Patriarch of Zen Buddhism – and here we begin to enter a more reliable chapter of history – was Hung-jen (601-675). Who was apparently the first of the patriarchs to have any large following, however, much overshadowed by his immediate successor Hui-neng (637-713), the sixth Patriarch, whose life and teaching mark the definitive beginning of truly Chinese Zen – of Zen as it flourished during what was later called “the epoch of Zen activity,” the latter two hundred years of the T’ang dynasty, from about 700 to 906. Hui-neng’s original satori (the Zen experienced awakening) occurred spontaneously, without the benefit of a master and that his biography represents him as an illiterate peasant. Apparently Hung-jen immediately recognized the depth of his insight, but fearing that his humble origins might make him unacceptable in a community of scholarly monks, the Patriarch put him to work in the kitchen compound.

Some time later, the patriarch announced that he was looking for a successor to whom he might transmit his office, together with the robe and begging bowl (said to have been handed down from the Buddha) which were its insignia. The honor was to be conferred upon the person who submitted the best poem, expressing his understanding of Buddhism. The chief monk of the community was then a certain shen-hsiu, and all the others naturally assumed that the office would go to him and so made no attempt to compete.

During the night Shen-hsiu, posted the following lines in the corridor near Patriarch’s quarter:

The body is like unto the Bodhi-tree,

And the mind to a mirror bright;

Carefully we cleanse them hour by hour,

Lest dust should fall upon them.

When Shen-hsiu came to the Patriarch, the following morning, in private and claimed the authorship, the Patriarch declared that his understanding was still far from perfect. Then, on the following day another poem appeared beside the first:

Originally there was no Bodhi-tree,

Nor was there any mirror;

Since Originally there was nothing,

Whereon can the dust fall?

The Patriarch knew that only Hui-neng could have written this, but to avoid jealousy he rubbed out the poem with his shoe, and summoned Hui-neng to his room secretly, by night. Here he conferred the patriarchate, the robe and the bowl upon him, and told him to flee into the mountains until the hurt feelings of the other monks had subsided and the time was ripe for him to begin his public teaching.

A comparison of the two poems shows at once the distinctive flavor of Hui-neng’s Zen. Shen-hsiu’s poem reflects what was apparently the general and popular view of dhyana practice in Chinese Buddhism. It was obviously understood as the discipline of sitting meditation, in which the mind was “purified” by an intense concentration which would cause all thoughts and attachments to cease. Taken rather literally, many Buddhist and Taoist texts would substantiate this view – that the highest state of consciousness is a consciousness empty of all contents, all ideas, feelings, and even sensations. Today in India this is a very prevalent notion of Samadhi (meditation).

Hui-neng’s position was that a man with an empty consciousness was no better than “a block of wood or a lump of stone.” He insisted that the whole idea of purifying the mind was irrelevant and confusing, because “our own nature is fundamentally clear and pure.” In other words, there is no analogy between consciousness or mind and a mirror that can be wiped. The true mind is “no-mind”, which is to say that it is not to be regarded as an object of thought or action, as if it were a thing to be grasped and controlled. To try to purify it is to be contaminated with purity. Obviously this is the Taoist philosophy of naturalness, according to which a person is not genuinely free, detached, or pure when his state is the result of an artificial discipline. He is just imitating purity, just “faking” clear awareness.

Hui-neng’s position was that a man with an empty consciousness was no better than “a block of wood or a lump of stone.” He insisted that the whole idea of purifying the mind was irrelevant and confusing, because “our own nature is fundamentally clear and pure.” In other words, there is no analogy between consciousness or mind and a mirror that can be wiped. The true mind is “no-mind”, which is to say that it is not to be regarded as an object of thought or action, as if it were a thing to be grasped and controlled. To try to purify it is to be contaminated with purity. Obviously this is the Taoist philosophy of naturalness, according to which a person is not genuinely free, detached, or pure when his state is the result of an artificial discipline. He is just imitating purity, just “faking” clear awareness.

Hui-neng’s teaching is that instead of trying to purify or empty the mind, one must simply let go of the mind – because the mind is nothing to be grasped. Letting go of the mind is also equivalent to letting go of the series of thoughts and impressions which come and go “in” the mind, neither repressing them, holding them, nor interfering with them.

Thoughts come and go of themselves, for through the use of wisdom there is no blockage. This is the samadhi (contemplation) or prajna (wisdom), and natural liberation. Such is the practice of “no-thought”. But if you do not think of anything at all, and immediately command thoughts to cease, this is to be tied in a knot by a method, and is called an obtuse view.

Of the usual view of meditation practice he said:

To concentrate on the mind and to contemplate it until it is still is a disease and not dhyana. To restrain the body by sitting up for a long time – of what benefit is this towards the Dharma?

And again:

If you start concentrating the mind on stillness, you will merely produce an unreal stillness….What does the word “meditation” means? In this school it means no barriers, no obstacles; it is beyond all objective situations whether good or bad. The word “sitting” means not to stir up thoughts in the mind.

In counteracting the false dhyana of mere empty-mindedness, Hui-neng compares the Great Void to space, and calls it great, not just because it is empty, but because it contains the sun, moon, and the stars. True dhyana is to realize that one’s own nature is like space, and that thoughts and sensations come and go in this “original mind” like birds through the sky, leaving no trace. Awakening, in his school, is “sudden” because it is for quick-witted rather than slow-witted people. The latter must of necessity understand gradually, or more exactly, after a long time, since the sixth Patriarch’s doctrine does not admit of stages or growth. To be awakened at all is to be awakened completely, for, having no parts or divisions, the Buddha nature is not realized bit by bit. His final instructions to his disciples contain an interesting clue to the latter development of the mondo or “question-answer” method of teaching:

In counteracting the false dhyana of mere empty-mindedness, Hui-neng compares the Great Void to space, and calls it great, not just because it is empty, but because it contains the sun, moon, and the stars. True dhyana is to realize that one’s own nature is like space, and that thoughts and sensations come and go in this “original mind” like birds through the sky, leaving no trace. Awakening, in his school, is “sudden” because it is for quick-witted rather than slow-witted people. The latter must of necessity understand gradually, or more exactly, after a long time, since the sixth Patriarch’s doctrine does not admit of stages or growth. To be awakened at all is to be awakened completely, for, having no parts or divisions, the Buddha nature is not realized bit by bit. His final instructions to his disciples contain an interesting clue to the latter development of the mondo or “question-answer” method of teaching:

If, in questioning you, someone asks about being, answer with non-being. If he asks about non-being, answer with being. If he asks about the ordinary man, answer in terms of the sage. If he asks about the sage, answer in terms of the ordinary man. By this method of opposites mutually related there arises an understanding of the Middle Way. For every question that you are asked, respond in terms of its opposite.

Hui-neng died in 713, and with his death the institution of Patriarchate ceased, for the genealogical tree of Zen put forth branches. Hui-neng’s tradition passed to five disciples. The spiritual descendants of a couple of them live on today as two principal schools of Zen in Japan, the Rinzai and the Soto.

The writing and records of Hui-neng’s successors continue to be concerned with naturalness. On the principle that “the true mind is no mind,” and “our true nature is no (special) nature,” it is likewise stressed that the true practice of Zen is no practice, that is, the seeming paradox of being a Buddha without intending to be a Buddha.

Source: The way of Zen, by: Alan W. Watts