Historically, Zen may be regarded as the fulfillment of long traditions of Indian and Chinese culture, though it is actually much more Chinese than Indian, and since the twelfth century, it has rooted itself deeply and most creatively in the culture of Japan. The Rinzai School of Zen was introduced into Japan in 1911 by the Japanese T’ien-tai monk Eisai (1141-1215), who established monasteries at Kyoto and Kamakura under imperial patronage.The Soto School was introduced in 1227 by the extraordinary jenius Dogen (1200-1253), who established the great monastery of Eiheiji, refusing, however, to accept imperial favors. It should be noted that Zen arrived in Japanshortly after the beginning of the Kamakura Era, when the military dictator Yoritomo and his samurai followers had seized power from the hands of the then somewhat decadent nobility. This historical coincidence provided the military class, the samurai, with a type of Buddhism which appealed to the strongly because of its practical and earthy qualities and because of the directness and simplicity of its approach. Thus there arose that peculiar way of life called bushido, the Tao of the warrior, which is essentially to the arts of war. The association of the peace-loving doctrine of the Buddha with the military arts has always been a puzzle to Buddhists of other schools. It seems to involve the complete divorce of awakening from morality. But one must face the fact that, in its essence, the Buddhist experience is a liberation from conventions of every kind including the moral conventions. On the other hand Buddhism is not a revolt against convention, and in societies where the military caste is an integral part of the conventional structure and the warrior’s role an accepted necessity Buddhism will make it possible for him to fulfill that role as a Buddhist. The medieval cult of chivalry should be no less of a puzzle to the peace-loving Christian.

Historically, Zen may be regarded as the fulfillment of long traditions of Indian and Chinese culture, though it is actually much more Chinese than Indian, and since the twelfth century, it has rooted itself deeply and most creatively in the culture of Japan. The Rinzai School of Zen was introduced into Japan in 1911 by the Japanese T’ien-tai monk Eisai (1141-1215), who established monasteries at Kyoto and Kamakura under imperial patronage.The Soto School was introduced in 1227 by the extraordinary jenius Dogen (1200-1253), who established the great monastery of Eiheiji, refusing, however, to accept imperial favors. It should be noted that Zen arrived in Japanshortly after the beginning of the Kamakura Era, when the military dictator Yoritomo and his samurai followers had seized power from the hands of the then somewhat decadent nobility. This historical coincidence provided the military class, the samurai, with a type of Buddhism which appealed to the strongly because of its practical and earthy qualities and because of the directness and simplicity of its approach. Thus there arose that peculiar way of life called bushido, the Tao of the warrior, which is essentially to the arts of war. The association of the peace-loving doctrine of the Buddha with the military arts has always been a puzzle to Buddhists of other schools. It seems to involve the complete divorce of awakening from morality. But one must face the fact that, in its essence, the Buddhist experience is a liberation from conventions of every kind including the moral conventions. On the other hand Buddhism is not a revolt against convention, and in societies where the military caste is an integral part of the conventional structure and the warrior’s role an accepted necessity Buddhism will make it possible for him to fulfill that role as a Buddhist. The medieval cult of chivalry should be no less of a puzzle to the peace-loving Christian.

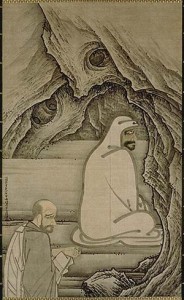

The contribution of Zen to Japanese culture has by no means been confined to bushido. It has entered into almost every aspect of people’s life – their architecture, poetry, painting, gardening, their athletics, crafts, and trades; it has penetrated the everyday language and thought of the most ordinary folk. For by the jenius of such Zen monks as Dogen, Hakuin, and Bankei, by such poets as Ryokan and Basho, and by such a painter as Sessho, Zen has been made extraordinary accessible to the common mind.

Dogen, in particular, made an incalculable contribution to his native land. His immense work, the shobogenzo (“Treasury of the Eye of the True Doctrine”), was written in the vernacular and covered every aspect of Buddhism from its formal discipline to its profoundest insights. His doctrine of time, change, and relativity is explained with the aid of the most provoking poetic images. Hakuin (1685-1768) reconstituted the koan* system, and is said to have trained no less than eighty successors in Zen. Bankei (1622-1693) found a way of presenting Zen which such ease and simplicity that it seemed almost too good to be true. He spoke to large audiences of farmers and country folk, but no one “important” seems to have dared to follow him.

We are at loss for parallels from other cultures for comparison, and the western student can best catch the flavor of Zen through observing the works of art which it was subsequently to inspire. The best image might be a garden consisting of no more than an expanse of raked sand, as a ground for several unhewn rocks overgrown with lichens and moss, such as one may see today in the Zen temples in Tokyo. The media are the simplest imaginable; the effect is as if man had hardly touched it, as if it had been transported unchanged from the seashore; but in practice only the most sensitive and experienced artist can achieve it. This sounds, of course, as though “Zen flavor” were studied and affected primitivism. Sometimes it is. But the genuine Zen flavor is when a man is almost miraculously natural without intending to be so. His Zen life is not to make himself but to grow that way.

* Kung-an (Japanese, koan) or “Zen problem,” literally, this term means a “public document” or “case” in the sense of a decision creating a legal precedent. Thus the koan system involves “passing” a series of tests based on the mondo or anecdotes of the old masters.

Source: The way of Zen, by: Alan W. Watts