The linear one-at-a-time character of speech and thought is particularly noticeable in all languages using alphabets, representing experience in long strings of letters. It is not easy to say why we must communicate with others (speak) and with ourselves (think) by this one-at-a-time method, life itself does not proceed in this cumbersome, linear fashion, and our own organisms could hardly live for a moment if they had to control themselves by taking thought of every breath, every beat of the heart, and every neutral impulse.

The linear one-at-a-time character of speech and thought is particularly noticeable in all languages using alphabets, representing experience in long strings of letters. It is not easy to say why we must communicate with others (speak) and with ourselves (think) by this one-at-a-time method, life itself does not proceed in this cumbersome, linear fashion, and our own organisms could hardly live for a moment if they had to control themselves by taking thought of every breath, every beat of the heart, and every neutral impulse.

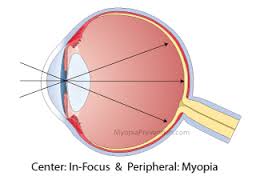

But if we are to find some explanation for this characteristic of thought, the sense of sight offers a suggestive analogy. For we have two types of vision, central and peripheral, not unlike the spotlight and floodlight. Central vision is used for accurate work like reading, in which your eyes are focused on one small area after another like spotlights. Peripheral vision is less conscious, less bright than the intense ray of the spotlight. We use it for seeing at night, and for taking “subconscious” notice of objects and movements not in the direct line of central vision. Unlike the spotlight, it can take in very many things at a time.There is then an analogy – and perhaps more than mere analogy – between central vision and conscience, once-at-a-time thinking, and between peripheral vision and the rather mysterious process which enables us to regulate the incredible complexity of our bodies without thinking at all. It should be noted, further, that we call our bodies complex as a result of trying to understand them in terms of linear thought, of words and concepts. But the complexity is not so much in our bodies as in the task of trying to understand them by this means of thinking. It is like trying to make out the features of a large room with no other light than a single bright ray. It is as complicated as trying to drink water with a fork instead of cup.

But if we are to find some explanation for this characteristic of thought, the sense of sight offers a suggestive analogy. For we have two types of vision, central and peripheral, not unlike the spotlight and floodlight. Central vision is used for accurate work like reading, in which your eyes are focused on one small area after another like spotlights. Peripheral vision is less conscious, less bright than the intense ray of the spotlight. We use it for seeing at night, and for taking “subconscious” notice of objects and movements not in the direct line of central vision. Unlike the spotlight, it can take in very many things at a time.There is then an analogy – and perhaps more than mere analogy – between central vision and conscience, once-at-a-time thinking, and between peripheral vision and the rather mysterious process which enables us to regulate the incredible complexity of our bodies without thinking at all. It should be noted, further, that we call our bodies complex as a result of trying to understand them in terms of linear thought, of words and concepts. But the complexity is not so much in our bodies as in the task of trying to understand them by this means of thinking. It is like trying to make out the features of a large room with no other light than a single bright ray. It is as complicated as trying to drink water with a fork instead of cup.

In this respect, the Chinese written language has a slight advantage over our own, and is perhaps symptomatic of a different way of thinking. It is still linear, still a series of abstractions taken in one-at-a-time. But its written signs are a little closer to life than spelled words because they are essentially pictures, and, as a Chinese proverb puts it, “ One showing is worth hundred sayings.” Compare, for example, the ease of showing someone how to tie a complex knot with the difficulty of telling him how to do it in words alone.

Now the general tendency of the Western mind is to feel that we do not really understand what we cannot represent, what we cannot communicate, by linear signs – by thinking. We are like “wallflowers” who cannot learn a dance unless someone draws him a diagram of the steps, who cannot “get it by the feel.” For some reason we do not trust and do not fully use “peripheral vision” of our minds. We learn music, for example by restricting the whole range of tone and rhythm to a notation of fixed tonal and rhythmic intervals – a notation which is incapable of representing Oriental music. But the Oriental musician has a rough notation which he uses only as a reminder of a melody. He learns music not by reading notes, but by listening to the performance of a teacher, getting the “feel” of it, and copying him, and this enables him to acquire rhythmic and tonal sophistications matched only by those Western jazz artists who use the same approach.

We are not suggesting that westerners simply do not use the “peripheral mind.” Being human we use it all the time, and every artist, every workman, every athlete calls into play some special development of its powers. But it is not academically and philosophically respectable. We have hardly begun to realize its possibilities, and it seldom, if ever, occurs to us that one of its most important uses is for that “knowledge of reality” which we try to attain by the cumbersome calculations of theology, metaphysics and logical inference.

Source: The way of Zen, by: Alan W. Watts